What It Really Means to Live in an “Art Town,” Population 335

By Erika Nelson

From 1907 to 1928, S. P. Dinsmoor, a retired Civil War Veteran and sculptor built the Cabin Home and Garden of Eden just on the outskirts of Lucas, Kansas. He was in his 60s when he started creating his fascinating, and bizarre, sculpture garden, located within walking distance of Main Street, visible from the railroad track, and intended as a source of income. With its three-story politically infused sprawling concrete sculptural vignettes depicting Freethought and Farmers Alliance tenets, his Cabin Home and Garden of Eden were popular attractions and provided financial security for Dinsmoor and his family.

S.P. Dinsmoor’s Garden of Eden in Lucas, Kansas. Dinsmoor used cement and limestone to create the eleven-room limestone “log” cabin home and the 150 surrounding sculptures. Photo courtesy of Erika Nelson.

It was just the beginning. A legacy. A promise. Today, Lucas, Kansas, is a tiny Art Town, population 335, with a century-old timeline of creative public expression.

From rural town to art destination

What does it mean to live in an Art Town? Meet the artists cultivating community in rural Kansas, and continuing to nurture the creative spirit in Lucas.

Since Dinsmoor established one of the country’s oldest artist-built environments at the edge of town, Lucas has been the site of a string of environments and creative endeavors that defy easy classification.

Built by folks without formal training, these grassroots art attractions continue to inspire both visitors and locals, well beyond the site-makers lifespans. Lucas had an unusually large number of such environments in addition to the Garden of Eden—Roy and Clara Miller’s Park of geological wonders, Florence Deeble’s three-dimensional postcard scenes of her favorite places anchoring her backyard rock garden, and Ed Root’s object encrusted cement statuary dotting his rural farmstead.

Roy and Clara Miller’s Park Mountain. Photo by Erika Nelson.

All of these formed the basis for an active arts tourism trade that serves as one piston in Lucas’ economic engine, but beyond the draw for outside eyes, the accessibility of materials, the embracing of creation as an acceptable form of expression for absolutely anyone, these public art works have drawn artists to not only visit, but relocate and become an active forces in the community.

The Garden of Eden drew me here in 2003, with ceramicist Eric Abraham (1936–2013) following shortly after in 2004. We were the first of the new generation of artists basing their practice with Lucas as a home, with Eric developing one of the first artist-spaces as a part of Lucas’ commercial district, and growing his Flying Pig Studio in a former Chevrolet dealership. Locals who had shared coffee and gossip at the shop found themselves still welcome to sit and gab in the mornings on the same vinyl upholstered couches. They learned about Eric’s process, and saw the labor involved in the often mysterious world of art-making.

His open process (and open doors) served as a direct illustration of artwork as work—the labor of art-making—the business of art in a commercial context.

Part of Lucas’s creative activation includes developing external-facing resources, like galleries that are open to the public for the selling of artwork, museums that tell visitors the story of the town. But it has also included internal structures and intangibles that artists need to live and thrive—space to create, access to materials, and mutual support.

I wrote about Lucas, Kansas, as a case study in Grassroots Growth of Creative Cultures in 2017 as a peek into the complicated models found in rural public art scenes. Since that time, the seeds sown by our artists and creators have even more fully taken root, transforming the two-block downtown into a creative corridor. That creative corridor is created by artists and makers who find the hollow spots and fill them from within, rather than relying on a developer to force a shift.

More than a roadside attraction, a true art community

Some artist-run spaces are outward-facing, open to the public, with other spaces developed as part of the internal-facing support systems.

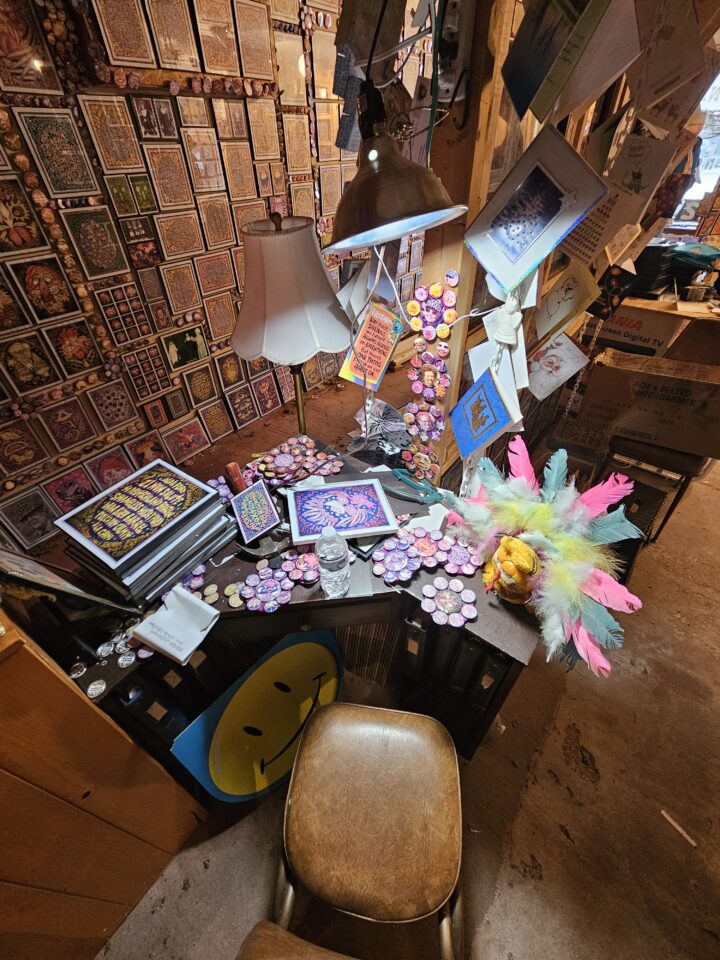

On April Fools Day 2016, artist Alan Vopat started a new tradition, opening his DaDa Muse’m at the north end of Main Street. Alan picked that particular date as a fail-safe. If he opened, he opened. If he didn’t, then it could be regarded as an elaborate hoax.

Alan Vopat’s seat of creation at his Dada Muse’m in Lucas, Kansas. Photo by Erika Nelson.

Since then, every April 1 sees another creative space opening or being dedicated: a Roadside Sideshow Expo, Old Blue Studio and Proving Grounds, Switchgrass Artist Co-Op, Woodpecker Archives, Standing Dog Studio and Gallery, an as-yet-unnamed photography studio, and writing workshops guided by local author Lori Brack.

It’s a mix of new residents and legacy owners reimagining spaces for creative entrepreneurs, changing the face of Main Street as the artist population grows.

Part of the April 1 event is for the public (now dubbed April Fools-A-Palooza), but the fertilization of the artist community happens during the artists’ walk—a mutual exploration of each other’s work areas the night before, visiting each space in a progressive sharing of snacks and spaces. Seeing where the magic happens, sharing ideas, and communing.

Grassroots magic, more than economic impact

It’s become the norm to talk about the economic impact of artists, often overshadowing the core of what is actually valuable in an arts community. Without the artists creating their work, the artists sharing their work, or the artists nurturing and creating mutual resources supporting creative work, Lucas, Kansas, would just be another Art Town, a shiny but shallow pass-through.

But that’s not our story. We’ve created something deeper, more meaningful.

The artists drawn to Lucas are here to create community, in an unexpected intersection of place and opportunity on the high plains.

- Artist Lori Brack’s Zine Workshop

- Two dogs at LeAnne Doljek’s Standing Dog Studio

- Jeff Shirley and Lacie Austin at Switchgrass Art Cooperative

All photography by Erika Nelson.